Our team of INI430 students, the Regent Turtles, were interested in studying how faith was reflected in the built environment of Regent Park, and how places of worship, in particular, integrate into the community. In order to answer these questions, we observed how five religious places in Regent Park share spaces with other institutions, such as non-religious schools, commercial businesses or even other places of worship. The importance of the urban issue we study is crucial because “for religious minorities, their religious buildings represent religious identity and power and are, therefore, linked to processes of emancipation or integration” (Verkaaik, 2013, p.8). Our mission is to support interfaith dialogue, through informing people from the Regent Park community, as well as those outside of it, on how the city of Toronto provides space for worship in Regent Park, and how those spaces are shared with other institutions. This is particularly important information, because a “variety of services, [including places of worship], has emerged in Toronto’s East Downtown because of the high concentration of low-income residents living there” (August, 2014, p.1323). We recognize the important connections between faith and community agency among low-income households, especially amid substantial impacts of recent urban change. While the built form was transformed by Regent Park’s revitalization project, houses of worship served as anchors in the neighbourhood, providing communities of faith with a continuity of organizing power and solidarity initiatives. But in also recognizing the many challenges that have arisen during the revitalization of Regent Park, have places of worship been appropriately accommodated similarly to community and civic institutions? This assessment of faith and non-faith spaces in the public sphere was important for us to analyze.

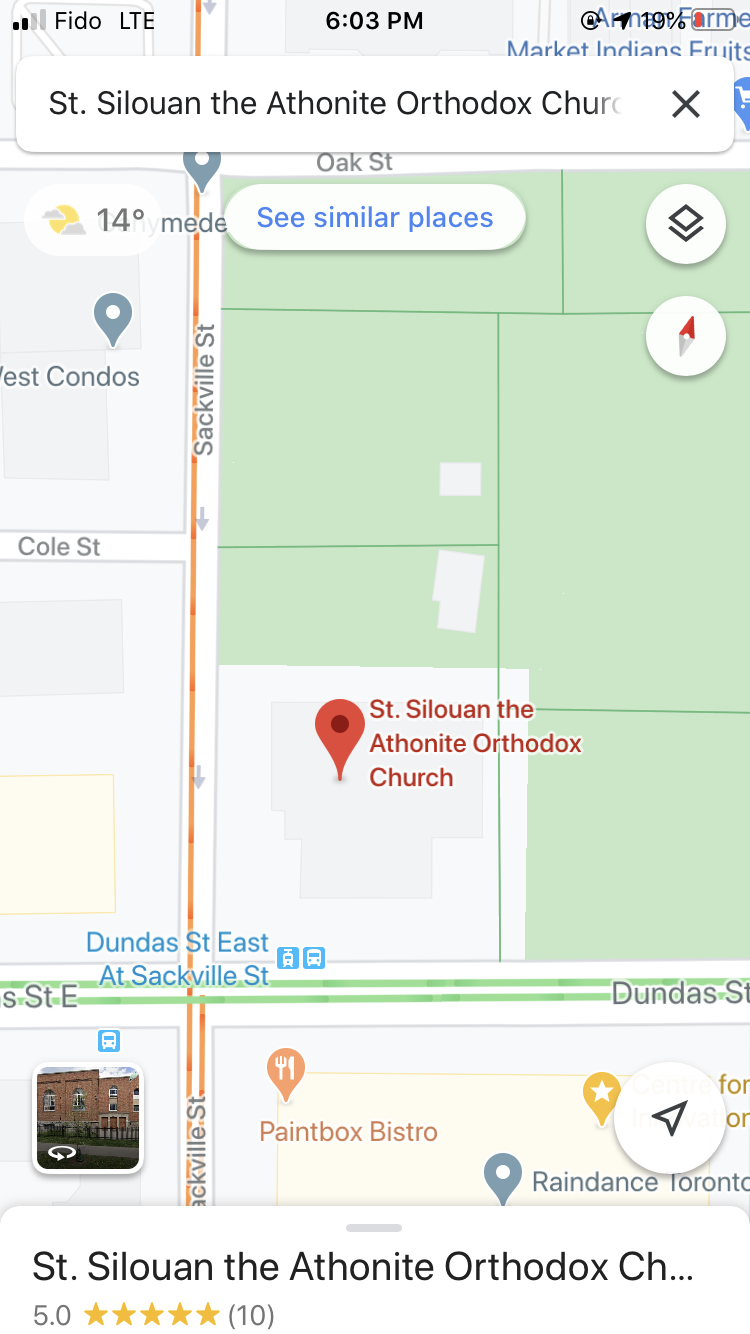

The approach our team used to study places of worship was to begin with field trips to the urban environments in which they were located. This was to observe their immediate surroundings, understand how building complexes operated in the neighbourhood, and determine how they interact with each other, as well as with other institutions in the vicinity. Once we had developed some reflections about these contexts, we sent interview questions using the publicly-available contact information to the houses of worship. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing measures in the region, this change to our information gathering occurred as we could no longer travel to Regent Park. Finally, with some changes to our final project, we supplemented our collected information with further online research regarding the churches and mosques of interest. After completing our research, out of the five worship places our team studied, only St. Bartholomew's Anglican and St. George's Macedonian Bulgarian Eastern Orthodox Churches stand as separate buildings, without sharing space physically with other institutions. However, St Cyril & Methody Macedonian-Bulgarian Eastern Orthodox and St Silouan the Athonite Orthodox Churches are housed together in the same physical church space on 237 Sackville St, together with a non-religious pre-school. Although each institution has a different entrance, they still share one building complex and the yard around it. Two other mosques that we studied, Masjid Omar Al Khattab and Masjidur Rahmah, share a building complex with commercial stores, conveniences, and restaurants due to their location on the retail strip on Parliament Street at the western edge of the neighbourhood.

Masjid Omar Bin Al-Khatab on Parliament Street, integrated with local businesses like ‘Hyderabad Palace’

Freestanding church building at 237 Sackville Street, housing both Sts. Cyril and Methody Eastern Orthodox Church, and St. Silouan Orthodox Church

Our first ideas regarding our project landed at developing both a photo essay and a ‘guidebook’ for worship places in the Regent Park neighbourhood. With the theme of faith and the built environment, all four of us agreed that presenting the buildings themselves told the story most vividly. Regarding the intended exhibition at the end of the term, we also agreed that both media products should have physical copies, in order to be able to distribute them to community members in attendance. However, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and with the last half of the course moved online with social distancing orders in place, we decided to keep only the guidebook as our final product, and redirect our perspective from an analysis of securitization to the story of inclusion. Our guiding call became the question: “how do places of worship share space in the community?” This is an important question for understanding the role of faith in cities: in particular, how intersectional identities, like religion and culture, interact with and integrate into civic and neighbourhood institutions. These interactions form the basis for community residents to live in and experience the neighbourhood. We aimed to provide an introduction to those within and outside the community of the various places of worship in the neighbourhood from a creative perspective. In most cases, guidebooks serve as a tool for tourists traveling to a new locale. It is also recognized that including places of worship in such a guidebook serves as cultural recognition for the religions present in the area (Jacobs, 2001, p.309). By documenting the places of worship in our brochure, we can document the role faith plays in Regent Park as a neighbourhood. In our plan, the brochure should serve more than as part of a research project, but also a piece of community information to anyone interested in Regent Park and its practice of faith.

Thus, we aim for our project to serve two goals. The first is a critical reflection on how worship places share physical space in the neighbourhood. By answering this question, we are able to provide comprehensive insights into the role that each house of worship plays in the neighbourhood. Some of them offer their halls for rent to the community; some of them run events for people in the community, regardless of the faith they practice (or lack thereof); some of them share space with non-religious institutions; or even another religious congregation in the same building. In this special time of a global pandemic, the definition of ‘space’ has additionally expanded to include online space. As a result of this unique time, we also document various efforts each house of worship has attempted in providing online spaces for their regular attendees through the adoption of social media. The second goal of our project as a whole is to display and distribute information about these worship places to the general public as a means of fostering interfaith dialogue. The target audience of our brochure is residents of Regent Park interested in its religious composition, as well as others who are interested in the history of faith and cultural diversity in the city of Toronto. It is our hope that for residents of Regent Park, our guidebook provides new pieces of information about the places they might often walk by, but have not yet had the opportunity to visit and learn more about. Irrespective of their own practices of faith or of no faith, we believe that building community cohesion requires a firm understanding of those who comprise it, and the guidebook provides a detailed look into how the community comes together in ways unique to Regent Park itself.

“Hall for rent” sign located outside the building of St. George’s Macedono-Bulgarian Eastern Orthodox Church in Regent Park

In producing this guidebook, amid the chaotic semester, our changing patterns of thought revealed much about how our perceptions of Regent Park had changed. With the first dialectic of securitization and inclusion that we began our research with, we often found ourselves focusing on the built form of religious institutions alone, without appreciating their context in the broader urban realm. Of course, this fell under standard research on securitization theory and the impact of social policies of state-centric “surveillance” particularly affecting the Muslim diaspora in communities of the West, like Toronto (Tiilikainen, 2005, p.53). However, Regent Park’s unique urban framework reveals more than this simplistic narrative. In focusing our later work on the ways in which spaces are inclusively shared, our understanding of the role of religion in urban space also expanded to include the conventional lifestyles associated with practicing faith. Spaces like schools, supermarkets, restaurants, and convenience stores became just as much a part of the story of faith in Regent Park as the houses of worship themselves. In some ways, this provided us with space to reflect on what it means to be a community member, and a citizen in civic, urban, and ethnocultural terms. To some extent, assuming these multiple identities is a complicated reality: the relationships residents form between their place of worship and neighbouring community hubs in Regent Park are a microcosm of Toronto’s larger negotiations of space in its multicultural aspirations.

To conclude this conversation on religion in Regent Park’s built form, it only seems appropriate to convey what the buildings tell us about where the neighbourhood is moving. Amid the rapid changes Regent Park is experiencing, its historic spaces of faith are shifting to provide new opportunities for community events and dialogue, and its newest spaces of faith are integrating themselves into the web of local institutions. In a neighbourhood representative of Toronto’s incredible diversity, there is no one story of religion in Regent Park. Successive generations of faith have negotiated and carved space to practice their faith in solidarity with their migrant communities in the neighbourhood, and as they have settled, those spaces have come to co-exist and create new connections. While they still perform the crucial role of supporting the unique spiritual needs of their respective communities, houses of worship are increasingly telling the story of Regent Park itself: a story that is dynamic, complex, ever-evolving, and most of all, accepting.

See the full guidebook here.

The Regent Turtles are Kamila, Rushay, Xinyi, and Huda.

References

August, M. (2014). Challenging the rhetoric of stigmatization: the benefits of concentrated poverty in Toronto's Regent Park. Environment and Planning A, 46(6), 1317-1333.

Jacobs, C. (2001). Folk for Whom? Tourist Guidebooks, Local Color, and the Spiritual Churches of New Orleans. The Journal of American Folklore, 114(453), 309-330. doi:10.2307/542025

Manouchehrifar, B. (2018). Is Planning ‘Secular’? Rethinking Religion, Secularism, and Planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(5), 653-677.

Tiilikainen, M. (2015). Looking for a Safe Place, Journal of Religion in Europe, 8(1), 51-72. doi: https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1163/18748929-00801004

Verkaaik, O. (2013). Religious Architecture: Anthropological Perspectives. In Verkaaik O. (Ed.), Religious Architecture: Anthropological Perspectives (pp. 7-24). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wp6sx.3